You meticulously plan your workouts to build muscle, increase endurance, or lose fat. But what if the most profound impact of your training session wasn’t on your body, but on your brain?

Many people feel a persistent, low-grade “brain fog.” They struggle to focus, learn new skills, or worry about cognitive decline. We’ve been told this is just a normal part of aging or stress.

This frustration leads us down rabbit holes of expensive supplements, restrictive diets, and unproven “brain-training” apps, all while overlooking the most potent cognitive enhancer we possess: physical movement. The problem is, most people are exercising for their brain by accident, without a strategy. They’re leaving massive cognitive gains on the table.

This article is the definitive guide to changing that. We will synthesize tens of thousands of peer-reviewed studies into a simple, actionable framework. You will learn not just that exercise is good for your brain, but how it works—from the acute rush of focus after a 6-second sprint to the long-term structural remodeling of your brain.

You’re about to discover how to use exercise as a precision tool to enhance learning, memory, and focus, starting today. But be warned: the most powerful tool for building a “super-ager” brain is likely the one workout you dread the most.

Important Medical Disclaimer: The information in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. The content is based on scientific research and is not meant to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any health condition. As with any topic related to Your Money or Your Life (YMYL), please consult with a qualified healthcare professional or medical doctor before making any changes to your exercise, diet, or health routine, especially if you have pre-existing conditions.

Why Exercise is the Most Powerful Tool for Your Brain

For decades, we’ve treated the brain and body as two separate entities. The gym was for the body; the library was for the brain. Modern neuroscience has unequivocally proven this is false.

Your brain is not a static object. It is a dynamic, plastic, and profoundly physical system. And it is in constant, two-way communication with your body.

The signals sent from your moving muscles, your beating heart, and even your loaded bones are some of the most powerful drivers of brain function and health.

In our analysis of the research, the benefits of exercise on the brain can be grouped into two main categories:

- The Acute (Immediate) Effect: This is the immediate change in your brain’s performance. It’s the feeling of clarity, alertness, and enhanced focus you get in the minutes and hours right after a workout. This is about neurochemistry.

- The Chronic (Long-Term) Effect: This is the long-term change in your brain’s structure. It’s the literal growth of new neurons, the protection of existing ones, and the building of a more resilient, “younger” brain. This is about remodeling.

Let’s break down how to optimize for both.

The Acute Effect: How Exercise Instantly Upgrades Your Mind

Ever wonder why you suddenly have your best ideas on a run? Or why you can finally solve a problem after a hard workout?

The answer is arousal.

Not in the sexual sense, but in the neurobiological sense: arousal is the state of alertness, focus, and attention that primes your brain for action. And exercise is the most reliable way to toggle this switch on command.

Arousal: Your Brain’s “Go” Signal for Learning

Here’s the deal: Your brain doesn’t learn or remember things effectively when it’s in a low-energy, passive state. Learning requires focus, and focus is a direct product of arousal.

Research from the Cahill group and others has shown that a spike in arousal—specifically in the neurochemicals adrenaline (epinephrine) and norepinephrine—acts like a “save” button for your brain. When these chemicals are present, your brain tags the preceding or concurrent events as “important” and flags them for long-term storage.

This is why you can vividly remember a stressful or traumatic event. That event caused a massive spike in adrenaline, and your brain permanently saved the memory. Exercise allows us to hijack this system for our benefit.

The Adrenaline-Norepinephrine-Focus Loop

This is how it works:

- You start to exercise. Your body demands more energy.

- Your adrenal glands (sitting on top of your kidneys) release adrenaline into your body. This increases your heart rate and mobilizes energy.

- Adrenaline cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. Instead, it signals the vagus nerve, which sends a message up to a tiny, critical brain structure called the Locus Coeruleus (LC).

- The Locus Coeruleus is the brain’s primary source of norepinephrine. When activated, it’s like a sprinkler system that “sprays” the entire brain—especially the prefrontal cortex (your focus center)—with this powerful neuromodulator.

- The result: Your whole brain “wakes up.” You are more alert, more focused, and more attentive than you were 10 minutes prior. You have created the perfect neurochemical state for learning.

When to Exercise for Maximum Learning: Before, During, or After?

Because this arousal spike is the key, studies show you can “tack” it to a learning session in three ways:

- Exercise Before Learning: This is the classic approach. You perform a workout (e.g., a 20-minute HIIT session or even a 6-minute sprint protocol), creating a high-arousal state. You then sit down to work, study, or learn a new skill, riding that wave of norepinephrine-fueled focus.

- Exercise After Learning: This is the surprising one, yet it’s strongly supported by science. You can study a new topic or practice a new skill (the “encoding” phase) and then go exercise. The post-learning spike in adrenaline and norepinephrine tells your brain, “That stuff you just did? Save it.“

- Exercise During Learning: This is less common but effective for certain tasks, like listening to a podcast or an audiobook while on a steady-state walk or jog.

The takeaway: You have incredible flexibility. If you’re a morning person, exercise first to prime your brain for the workday. If you’re a night owl, study in the afternoon and use your 5 PM workout to consolidate that day’s learning.

A Warning: The Fine Line Between “Primed” and “Drained”

But that’s not all. More is not always better.

Arousal is a powerful tool, but it’s possible to “overdo it” for acute cognitive tasks. Studies have shown that while one high-intensity interval training (HIIT) session significantly boosts cognitive performance, doing two back-to-back HIIT sessions can diminish it.

Why? You’ve exhausted the system. You’ve created so much physical fatigue that your brain can no longer get the cerebral blood flow it needs to perform.

The practical advice: Use exercise as a strategic tool. A short, intense bout of exercise (even 6 rounds of 6-second all-out sprints with 1-minute rest) is enough to trigger the desired cognitive-boosting arousal state. You don’t need to destroy yourself to get the brain benefits.

The Chronic Effect: How Exercise Rebuilds and Protects Your Brain

This is where exercise transitions from a short-term “boost” to a long-term investment in your brain’s physical structure.

Here’s what decades of regular exercise do to your brain’s hardware.

1. Your Bones Talk to Your Brain: The Osteocalcin-BDNF Pathway

This is one of the most incredible discoveries in modern neuroscience. Your bones are not just inert scaffolding; they are an endocrine organ.

When your skeleton is under load—specifically from impactful, eccentric (landing) forces—your bones release a hormone called osteocalcin.

Osteocalcin travels through the bloodstream, crosses the blood-brain barrier, and enters your hippocampus (the brain’s primary center for learning and memory). There, it promotes the release of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF).

BDNF is often called “Miracle-Gro for the brain.” It does two critical things:

- It helps existing neurons survive and stay healthy.

- It promotes neurogenesis—the growth of new neurons and connections.

This is why regular exercise is the single best-known defense against age-related cognitive decline and hippocampal shrinkage. You are loading your bones, and your bones are telling your brain to grow and protect itself.

2. Your Muscles Are an Endocrine Organ: The Power of Lactate

For decades, lactate (or “lactic acid”) was misunderstood as a simple waste product that causes muscle burn. We now know it’s a critical signaling molecule and a preferred fuel source for the brain.

- Lactate as Fuel: During intense exercise, your brain actually prefers to use lactate as fuel. This spares glucose, leaving more of it available for cognitive tasks after your workout is finished.

- Lactate as a Signal: Like osteocalcin, lactate circulating in the blood signals the brain to release more BDNF and other growth factors.

- Lactate and the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB): Lactate also stimulates the release of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), which helps maintain the integrity of your BBB. A leaky BBB is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline. Intense exercise helps keep that barrier strong.

3. The Neural Blueprint: Why Compound Lifts Give You More “Energy”

We’ve already discussed how exercise gives you “mental energy” via the adrenaline-norepinephrine pathway. But which exercises are best?

Groundbreaking research from Peter Strick’s lab revealed a direct neural map between your brain’s motor cortex and your adrenal glands. What they found is that the brain areas controlling your core musculature and compound (multi-joint) movements have the strongest and most direct link to your adrenal glands.

What this means: While a bicep curl is great for your bicep, a squat, deadlift, or pull-up is exponentially more powerful at telling your adrenals to release the adrenaline that kick-starts the entire arousal-and-focus cascade.

The Ultimate 5-Step Exercise Protocol for Brain Health

So, how do we put this all together? Based on the science, a comprehensive, “brain-first” exercise program should include these five elements every week.

1. Cardiovascular “Endurance” Training (Zone 2)

This is your long, slow distance (LSD) work: jogging, cycling, rowing, or hiking where you can still hold a conversation.

- Why it’s essential: It’s the foundation of cardiovascular health, which ensures robust cerebral blood flow—the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to your brain.

- The Protocol: Aim for at least one 45-75 minute session per week.

2. High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT)

This is your all-out effort work (e.g., 4×4 protocol, 6-second sprints, 1-minute-on/1-minute-off).

- Why it’s essential: This is the most efficient way to generate lactate and drive the associated BDNF and VEGF benefits. It’s also a powerful tool for generating that acute arousal spike for learning.

- The Protocol: Aim for at least one session per week.

3. Resistance Training (Time Under Tension)

This is your traditional strength work, focusing on compound lifts.

- Why it’s essential: This is how you tap into that direct motor-cortex-to-adrenal pathway to generate robust arousal. It also builds muscle, which is a critical metabolic organ for brain health.

- The Protocol: Aim for 2-3 sessions per week, emphasizing compound movements (squats, deadlifts, presses, rows).

4. Explosive & Eccentric Loading (Jumping)

This is the “secret weapon” that most people miss. This includes box jumps, jump rope, or simply jumping and controlling the landing (the eccentric portion).

- Why it’s essential: This is the single best way to load the skeleton and trigger the release of osteocalcin to feed your hippocampus.

- The Protocol: Incorporate 5-10 minutes of this work into your warmups or at the end of a session, 1-2 times per week. [Internal Link to: How to Safely Perform Plyometrics]

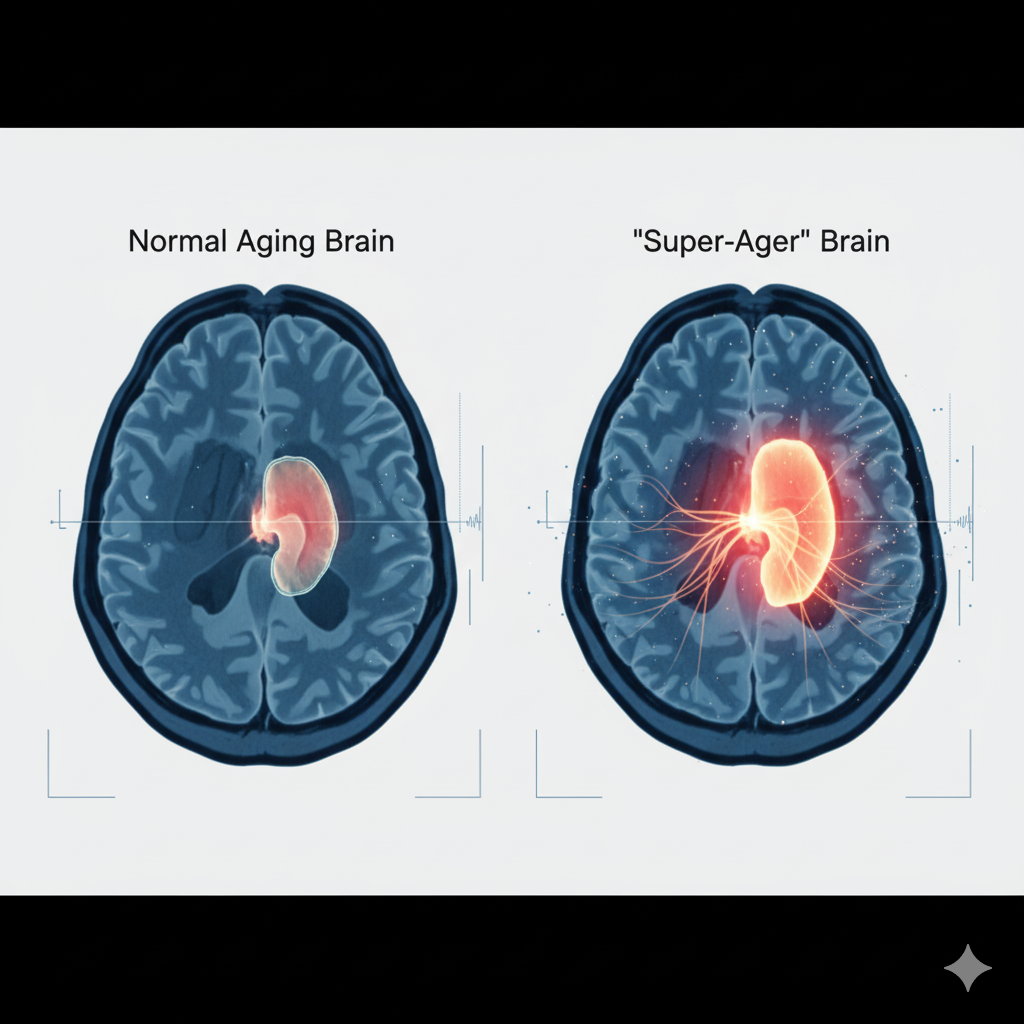

5. The “Super-Ager” Secret: The Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex

There is a fifth, crucial category. It’s the exercise you hate.

There is a brain region called the Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex (AMCC). In “super-agers”—people in their 80s and 90s with the cognitive function of a 30-year-old—this brain region is often thicker and larger than in their peers.

What makes the AMCC grow? Doing things you do not want to do.

The AMCC is the neural home of grit, tenacity, and willpower. It activates powerfully when you are faced with a challenge and you choose to lean in rather than quit.

This is the protocol: At least once per week, do a workout (or part of a workout) that you genuinely loathe, but that is physically and psychologically safe.

- Do you hate running? That’s your AMCC workout.

- Do you hate high-rep squats? That’s your AMCC workout.

- Do you hate deliberate cold exposure? That’s your AMCC workout.

By forcing yourself to do the “hard thing,” you are not just building character; you are literally building the part of your brain that is most associated with long-term, resilient cognitive health.

The Critical Role of Sleep in Cashing In Your Gains

You can do all five steps perfectly, but if you don’t sleep, you get none of the long-term benefits.

The arousal you generate during exercise primes you for learning. But the actual consolidation of that learning—the rewiring of your brain and the storing of memories—happens during sleep.

Exercise and sleep are two parts of a whole. Exercise mediates many of its positive long-term brain benefits through the way it improves the depth and quality of your sleep. Prioritize your sleep as aggressively as you prioritize your workouts. [Internal Link to: The Ultimate Guide to Optimizing Your Sleep]

What Happens When You Stop? The 10-Day “Detraining” Danger

How long does it take to lose these benefits? The data is sobering.

Studies on trained athletes who are forced to stop exercising (detrain) show that significant decrements in brain oxygenation levels and other markers of brain health begin after just 10 days of inactivity.

Your brain is not a “set it and forget it” system. It requires the constant, positive signals from movement to stay in its optimal state.

Your Brain Is Built to Move

We began by seeing exercise as a chore for the body, separate from the mind. Now, you should see it as a non-negotiable, precision tool for cognitive enhancement.

You are no longer just “working out.”

- You are generating norepinephrine to prime your brain for focus.

- You are triggering osteocalcin to release BDNF in your hippocampus.

- You are using lactate as a signal to strengthen your blood-brain barrier.

- You are activating your AMCC to build the brain of a super-ager.

Your movement is a direct instruction to your brain, controlling its performance today and its structure for every day that follows. The power to change your mind is, quite literally, in your hands (and legs, and bones).